African Culture and Traditions

Nzu and Ofo Rituals in Igbo Culture

An insight into Nzu and Ofo rituals in Igbo culture. Learn what nzu and ofo mean, their origins, how they are used in ceremonies, their spiritual and cultural importance, local differences, and how these practices survive or change today.

Across the towns and villages of Igboland, certain sacred objects carry deep meanings that go beyond what the eyes can see. Among these are Nzu, the sacred white chalk and Ofo, the revered staff of truth and ancestral authority. Together, they form the heart of many Nzu and Ofo rituals that define the moral, spiritual and social fabric of Igbo traditional life.

To Igbo people, nzu and ofo are not just physical objects; they are living symbols of purity, justice, peace and connection with the ancestors. They remind every individual that truth must guide actions and that purity of heart opens the way for blessings from both the gods and the forefathers.

Whether in welcoming a guest with a mark of nzu, sealing an oath with the ofo, or blessing a new leader, these two items bridge the visible and the invisible worlds.

Long before the coming of modern religion or law, Nzu and Ofo rituals shaped community order, preserved moral conduct and kept families tied to their roots. Even today, their quiet presence is felt at weddings, festivals, coronations and sacred gatherings. They speak of a people whose sense of right and wrong, life and afterlife, peace and justice are bound together in age-old tradition.

This article explores the meanings of nzu and ofo, their origins, how they are used in rituals, their cultural and spiritual significance, local variations, and how these practices continue to adapt in modern times.

It presents a clear and respectful look at how the Nzu and Ofo rituals continue to express the Igbo vision of life. Clean, truthful and connected to the ancestors.

Meaning of Nzu in Nzu and Ofo Rituals

Nzu

In Igbo culture, nzu refers to white chalk or white clay and holds deep symbolic meaning. The Igbo word “nzu” literally means white chalk, and in many traditions, it stands for purity, peace and a clean heart.

Because of its white colour, nzu is associated with cleanliness and moral integrity. It signals that a person or a space is free of wrongdoing or impurity and is ready for a respectful interaction with others or with the spiritual realm.

In Nzu and Ofo rituals use, nzu often appears in hospitality, welcoming a guest or showing that the host comes with no hidden ill-intent. Presenting nzu to a visitor or asking the visitor to mark the ground with it communicates trust, openness and goodwill.

In spiritual practices, nzu is used by diviners or ritual specialists as a marker of special sight or spiritual awareness. For example, applying chalk near the eyes signals the ability to see into the spirit world.

Nzu also features in cleansing and purification rites. When used to mark the body, a threshold, or a sacred spot, it acts as a symbol of separation from impurity or harm and a preparation for sacred activity.

In these ways, nzu is more than mere chalk; it is a tangible expression of values such as honesty, peace, cleanliness and spiritual readiness. It plays a role in daily life, in ceremony and in the relationship between the living, their community and their ancestors.

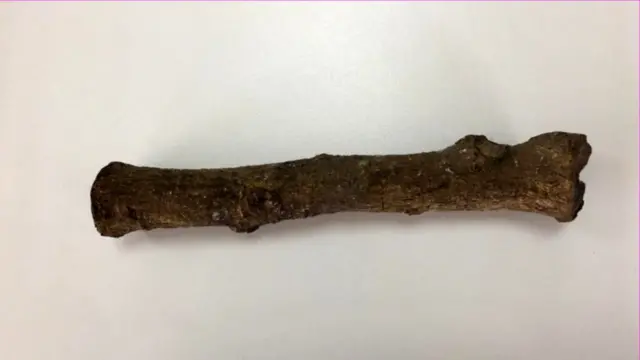

Meaning of Ofo in Nzu and Ofo Rituals

Ofo staff

In Igbo culture, the term ofo refers to a sacred staff or emblem that carries deep spiritual, moral and social significance. The ofo is normally made from a branch of the tree known botanically as Detarium elastica (sometimes cited as Detarium senegalense).

The ofo stands for truth, justice and authority. Among Igbo people, one common saying is ofo-na-ogu, meaning ofo and innocence (ogu), which together support the idea that rightful authority must rest on moral innocence or purity.

The ofo acts as a symbol of continuity between the living and the ancestors. When a family or lineage head is entrusted with the ofo, he becomes the custodian of the communal rights, mores and sacred traditions passed down by his forebears.

If someone holds the ofo during a ceremony, dispute settlement or oath-taking, it signals that what is said is bound by ancestral and spiritual witness. The presence of the ofo affirms that the decision or promise is not merely social but also cosmic.

In many communities, the ofo is, therefore, both a physical object and a living moral instrument. It embodies the values of honesty, fairness and collective responsibility.

To summarise, in Igbo tradition, ofo means the staff of truth and justice, the symbol of ancestral authority, the guardian of communal ethics and the link between the visible world of people and the invisible world of spirits and ancestors.

Origins and Background of Nzu and Ofo Rituals

The nzu and ofo rituals of Igbo culture rest on ancient foundations that entwine spiritual beliefs, social organization and moral order. Understanding how these rituals emerged helps us appreciate why they remain powerful today.

Origins of Ofo

The staff known as ofo is rooted in Igbo cosmology and social structure. The ofo is often made from a tree locally called osisi ofo, botanically identified as Detarium senegalense or Detarium elastica. Traditional accounts say that the branches used to make an ofo stick should fall naturally from the tree rather than being cut.

In theory, the authority carried by an ofo flows from the ancestors and from the Supreme Being (Chukwu) through lineage lines. One study stated that It is believed that in the heavenly compound of Chukwu, there is an ofo tree … Through this tree, the Supreme Being transmits blessing to creatures who occupy …

The ofo, therefore, originated as a symbol of divine and ancestral authority, transferred into the human community via family heads, elders and priests.

While the exact date of origin cannot be determined, scholars describe the ofo institution as shrouded in mystery. Yet, age-long among the Igbo. Among its functions in early societies were dispute settlement, ritual oath-taking and representing family, kindred and community rights.

Origins of Nzu

Ofo rituals

The ritual use of nzu (white clay or chalk) in Igbo culture also dates back deep into history, appearing in hospitality, purification and ritual marking. The white colour of nzu has long represented purity, peace and moral integrity in Igbo cosmology.

Nzu is used in marking sacred space, drawing ritual lines and signalling that a gathering or person is entering into a ritual state. One source explains that when Igbo elders meet, they each take white chalk and draw lines on the floor as part of the ritual offering and as witness to clean intent. Archaeological and cultural accounts suggest that chalk (or its local equivalent) has featured in Igbo ritual life for centuries.

Beyond ritual marking, nzu also found practical use in food preservation and body adornment. A study of edible chalk in an Igbo area noted that nzu (or locally consumed chalk) had been used from ages in celebrations such as childbirth, in preserving beans and for cultural adornment.

The Relationship Between the Nzu and Ofo Rituals

While nzu and ofo rituals are distinct, they frequently intersect in Igbo ceremonial life. Ofo, as the symbol of authority and truth often features in rituals where moral or social law is invoked such as oaths, dispute resolution or leadership installation. In those contexts, nzu may be used simultaneously to mark ritual cleanliness or sanctified space.

The origin of the combined ritual practice lies in the need for visible, tangible symbols by which moral, spiritual and social accountability could be realized in a largely oral society. Ofo supplied the moral/legal emblem. Nzu supplied the purity/spiritual mark. Together, they functioned to connect the living, the ancestors and the land in communal rites.

Historical Background and Evolution

Historically, Igbo people lived in small kin-group communities where lineage, kindred and village structures were organized around male elders and family heads. In those settings, the ofo belonged to the eldest male of the lineage or the community’s eldest elder. On his death, the ofo would typically pass to his successor, often the eldest son, through a ritual ceremony of transfer.

The nzu rituals emerged within the same social units as recorded markers of purity, hospitality, initiation and sacred space. For example, the use of nzu in initiation rites for young women in some communities has been documented.

With time, contact with Christianity, colonialism and modern State structures altered how ofo and nzu rituals were publicly practiced. Some of the legal functions of the ofo, for instance, were superseded by colonial or State courts. Some nzu uses (especially consumption of chalk) became controversial due to health risks. Yet, both rituals survived by adapting. This historical background shows that they are not relics but evolving traditions.

In principle, the origins and background of nzu and ofo rituals reflect a worldview in which morality, ancestry, spiritual cleansing and communal authority were intertwined. The ofo emerged as a symbol of truth, justice and ancestral authority while nzu emerged as a marker of purity, sanctified space and ritual readiness.

Over centuries, these practices became embedded in Igbo social life and continue today, though in adapted forms, as core elements of the nzu and ofo rituals.

How Nzu and Ofo Rituals are Used

Nzu and Ofo Ritual

Nzu and Ofo rituals are deeply woven into Igbo spiritual and social life. The use of these ritual objects brings together purification, moral accountability, communal welcome, title taking, dispute resolution and ancestral communion. Below are several major ways the Nzu and Ofo rituals play out in Igbo contexts.

Oath-taking, dispute resolution and covenant making

In many Igbo communities, the ofo staff is used to administer oaths or settle disputes. During the ritual, the ofo may be placed on the ground, held by the oath-taker, or laid out in front of the parties. The chief priest, elder or family head may strike the ofo on the earth to indicate the gravity of the promise and the presence of ancestral witness.

As one study noted, during dispute resolution, the striking of the ofo stick on the ground seals the swearing of the oath up with the declaration.

Nzu often appears alongside ofo in these rituals. For example, nzu may be rubbed on the hand or chest of the person about to swear the oath, or used to mark a clean ritual space. The presence of nzu signals that the participants approach the ancestor-and-spirit world with purified intent.

The combination of nzu and ofo rituals emphasizes both purity (nzu) and truthful binding with the ancestors (ofo). Therefore, nzu and ofo are core ingredients of many Nzu and Ofo rituals.

Purification, initiation and sacred marking

Nzu is widely used in purification and initiation rites. In many Igbo rituals, after physical cleansing, persons or objects are anointed with nzu to mark them as ready for sacred tasks, or to mark their transition into a new role. Nzu is applied to the body after a bath for purification. It is used in the activities of Igọ Ọfọ or Igọ Mmuọ to facilitate clear communication with one’s higher self and forces.

Nzu is also used to draw lines on the ground or mark surfaces in preparation for ritual performance. These marks define a sanctified space.

In ceremonies of title taking, for example when a young man becomes a titled elder, the ofo may be formally handed over, or placed before the new title holder, symbolizing the transfer of authority, and nzu may be used to purify the initiate or mark their new status. While explicit fieldwork is less frequent, the ritual use of ofo in title transfers is well attested.

Hospitality, welcome and community bonding

Nzu is often used in welcoming visitors to a community or household. In many parts of Igbo land, when a guest arrives, the host may present white chalk (nzu) and ask the guest to mark the visitor’s hand or forehead, or draw lines on the ground signifying mutual goodwill and peace. This use of nzu is part of Nzu and Ofo rituals in the wider social sphere. When a stranger visits a household, they are first presented with white Nzu. This ritual signifies the mutual reception with love, peace, happiness, and purity of heart.

Though the ofo itself is less common in everyday hospitality, its presence in a household or title-space reinforces that the space is under ancestral authority and moral obligations. In this way, Nzu and Ofo rituals overlap in marking social welcome under spiritual watch.

Divination, spiritual communication and ritual art

Nzu is also used by traditional healers (dibia) and ritual specialists to communicate with ancestors or the spirit world. For instance, nzu may be applied around the eyes of a diviner so that the practitioner may symbolically “see” into the spirit realm.

Ofo may also appear in ritual settings of prayer and sacrifice. It acts as a physical instrument linking the living to the ancestors. One study describes ofo as the baton in the relay race of the prayer life of the nation.

In many Nzu and Ofo rituals, items such as kola nut, alligator pepper, water, palm wine, nzu and ofo may all be present. The ofo may be struck or placed, the nzu applied or drawn, the kola nut broken, and prayers offered together. The combined ritual registers the moment as both socially binding and spiritually grounded.

Title taking, installation of leaders, and ancestral linkage

When a family, kindred or community installs a new leader, the ofo is often central. The holder of the ofo becomes the official custodian of family or community rights, traditions and moral order. The nzu, in parallel, is used to mark the leader’s purity of intent and readiness to serve. In title-taking, the ofo itself dramatizes the spiritual basis of even the most secular matters for the Igbo.

Thus, in many rites, the Nzu and Ofo rituals work side by side: the ofo underlines authority and ancestral continuity, the nzu underlines purity and welcome, and together they signal to the community that the leader now stands between the living and the dead.

In short, when exploring Nzu and Ofo rituals, one sees that they serve layered functions: purification, moral binding, hospitality, spiritual communication, leadership installation and communal justice. Their combined use reinforces both the social covenant (through ofo) and the moral or spiritual cleanliness (through nzu).

Spiritual and Cultural Significance of Nzu and Ofo Rituals

Nzu and ofo rituals hold deep spiritual and cultural meaning within Igbo society. These rites carry moral, communal and metaphysical weight. They bind individuals to ancestors, land and ethical standards. Below are several of the key aspects of how nzu and ofo rituals function spiritually and culturally.

Connecting with purity, ancestors and the earth

In Igbo cosmology, the earth is seen as a mother figure and source of life. The ritual use of nzu signifies purity, moral cleanliness and readiness for contact with the spiritual world. The chalk’s white colour marks the person or space as sanctified and open to ancestral or divine presence.

The ofo, in turn, symbolizes the authority of ancestors, the link between the living and the dead, and the presence of spiritual truth in the world of humans. When someone holds an ofo staff, they are seen as standing before both the ancestors and the Supreme Being as a custodian of moral law.

Together, in the nzu and ofo rituals, the white chalk purifies and clears the way, while the staff of authority compels truth and justice. This interplay shows that ritual in Igbo life is not just cosmetic but fundamentally ethical and spiritual.

Upholding truth, justice and communal morality

The ofo ritual object plays a central role in maintaining justice and moral order in the community. It signifies that those who wield it act not by personal whim but as representatives of collective rights and ancestral will. The bearer is expected to live in truth and fairness.

In parallel, nzu affirms the moral status of participants in ritual. When someone is marked with nzu, or when chalk is used to draw lines for a ritual space, it declares that the person or space is free from hidden malice and is ready for honest interaction.

Thus, in nzu and ofo rituals, the moral dimension of Igbo culture is expressed: purity and truth are prerequisites for community harmony and spiritual wellbeing.

Symbolizing identity, continuity and cultural resilience

Nzu and ofo rituals are cultural anchors. They link individuals to their lineage and community, and bind the past to the present. The ofo staff is often passed down through generations, signifying the unbroken chain of family rights, duties and origins.

Similarly, nzu use in hospitality, initiation, house blessings and festivals marks communal identity and shared values. For example, presenting nzu to a visitor signals the host’s commitment to peaceful, truthful fellowship.

In this way, nzu and ofo rituals serve both as spiritual practices and as cultural sign-posts that resist erosion by modernity. They maintain what it means to belong and what it means to act in right relation to ancestors and neighbours.

Mediating the invisible and visible worlds

One of the deepest layers of the spiritual significance of nzu and ofo rituals is their role in bridging the physical and metaphysical. Diviners and traditional healers use nzu chalk in ways that symbolize vision into the spiritual realm, e.g. by applying nzu around the eye for spiritual sight.

The ofo staff is seen as a channel through which ancestral forces and divine moral principles act in the world of the living. Decisions taken under its authority are believed to have spiritual consequences beyond the visible.

Hence, nzu and ofo rituals work on multiple levels: they enact moral and social order here, and they engage with unseen realms of ancestors and cosmic balance.

Cultural adaptation and modern significance

Though deeply traditional, nzu and ofo rituals remain alive and relevant. Many communities still use nzu in welcoming ceremonies, house blessings, festivals and naming rituals. Its symbolism of purity, goodwill and spiritual openness continues to resonate.

The ofo continues to function in many places as a symbol of community authority and moral consequence, even as formal courts and State law now also exist. Its spiritual and symbolic weight still informs local governance, rituals and social memory.

This way, the significance of nzu and ofo rituals is not only ancient but ongoing. They adapt, survive and persist as living parts of Igbo culture.

The spiritual and cultural significance of nzu and ofo rituals lies in their capacity to maintain purity, truth, ancestral connection, community identity, moral order and engagement with the spiritual world. They shape how individuals relate to each other, to their ancestors and to the land. They speak of values that are both personal and collective, seen and unseen.

Local Variation and Symbolic Layers in Nzu and Ofo Rituals

The rituals of nzu and ofo in Igbo culture are not uniform. They vary significantly from one locality, lineage or title system to another. These variations add rich symbolic layers that reflect local history, kinship structure, and spiritual emphasis. Understanding these nuances helps in fully appreciating how nzu and ofo rituals operate in different contexts.

Local variation in ofo practice

The staff known as ofo is widely used across Igbo communities, but the way it is made, held, and transferred differs locally. In some areas, the ofo is made from a branch of the tree botanically called Detarium elastica (or Detarium senegalense). Some communities insist that the branch used must fall naturally from the tree rather than being cut.

In other towns, the ofo may be made of wood, metal or bundled sticks, sometimes, adorned with feathers or coloured cloth.

Also, who holds the ofo and when it is passed on varies. In some patrilineal lineages, the eldest male becomes custodian; in others a titled man or priest may hold it

These differences are localiZed but important. They show how the ofo ritual space adapts to social structure, lineage rules and even settlement patterns.

Local variation in nzu use

Similarly, the use of nzu shows local variation in meaning and practice. In some communities, nzu is used primarily for hospitality, offering to a visitor as sign of welcome, trust and peace.

In other places, nzu is applied during initiation rites, purification ceremonies, body marking, or even daily spiritual practices. For example, the study of “igo ofo ututu” from a village in Imo State records nzu as part of the items laid out for the ritual.

The chalk may also be mixed or substituted by other local materials in some villages, or used in different colours based on local customs. The precise marks drawn or the gestures linked to it can differ.

All these variations reflect local sensibilities, resources, and symbolic priorities.

Symbolic layers emerging from variation

Because of the local variation, the symbolic meaning of nzu and ofo rituals becomes layered.

The ofo staff in one community may emphasize ancestral continuity and justice; in another community, it may emphasize leadership legitimacy and land rights. The underlying principle of truth and authority remains, but the emphasis shifts.

The nzu chalk may in one town primarily signal peace and hospitality; in another town it may signal purification, readiness for ritual, or even spiritual vision. These shifts add depth to how nzu is read in ritual.

The combination of nzu and ofo in the same ritual can produce varied symbolic effects. In some places, the nzu prepares the ground (spiritually and physically) and the ofo binds the promise or decision to the ancestors. In other places, the roles may invert slightly or additional items may be included.

Local idioms and sayings capture the symbolic layers. For example, the phrase ofo-na-ogu (autorithy and innocence) highlights how ofo ritual carries not just authority but the moral condition of innocence or purity.

These symbolic layers mean that someone observing nzu and ofo rituals must consider local context: the same objects can mean slightly different things in different towns.

Importance of recognizing local variation

Recognizing local variation and symbolic layering matters for a few reasons:

- It honours the diversity within Igbo culture rather than treating ritual as uniform. Different communities keep slightly different traditions, which is legitimate and important.

- It helps avoid misinterpretation when documenting or writing about nzu and ofo rituals. A ritual in Imo State may differ in detail from one in Anambra or Enugu.

- It makes clear that nzu and ofo rituals are living practices, not frozen relics. Their variation reflects adaptability to local social structure, environment and history.

- It supports cultural accuracy: when writing or teaching about nzu and ofo rituals, referencing specific communities adds credibility and precision.

The local variation and symbolic layers of the nzu and ofo rituals enrich their meaning in Igbo culture. While the core functions – purity, authority, ancestral link, moral binding remain consistent, the form, emphasis and interpretation differ by place. Appreciating these differences helps us understand ritual not as a single monolith but as a vibrant and varied tradition.

Contemporary Status and Adaptation

The rituals of nzu and ofo continue to evolve in modern Igbo society. While rooted in traditional spiritual and communal functions, they are being adapted to new social realities. Nzu and ofo rituals are being maintained, transformed or challenged in today Igbo society.

In many Igbo communities the ofo staff still retains symbolic authority in leadership, cultural events and community rites. Ofo staff is seen as a timeless symbol of authority, deeply ingrained in the cultural and spiritual fabric of Igbo society. Contemporary leaders can draw on the ofo’s symbolic power to highlight justice, accountability and service.

Similarly, nzu remains visible in cultural practices. In a review of its symbolism, nzu is described as continuing to signify purity, peace and sincerity, and is still used in traditional ceremonies, naming rituals, ancestral offerings and cultural revitalization efforts. This shows that the rituals involving nzu and ofo are being preserved, even as some forms shift.

The practice of nzu and ofo rituals is adapting to modern contexts in several ways. The ofo, while less central in formal legal dispute resolution in some places, is being referenced as a moral symbol in leadership and community governance today.

Nzu, once consumed as edible chalk in some cultural contexts, is now the subject of public health advice. A Nigerian nutritionist warned that calabash chalk (nzu) contains high levels of lead and other heavy metals and advised against its consumption. This health concern is causing shifts in how some nzu practices are managed or reinterpreted.

Some rituals combining nzu and ofo are being incorporated into cultural festivals, tourism and heritage programmes. By so doing, they serve not only spiritual or communal roles, but also cultural-education and identity functions. For instance, advocates of Igbo cultural heritage note that nzu’s symbolism is being promoted via cultural advocacy groups and social media.

The contemporary status of nzu and ofo rituals is not without challenges, though. The historical role of ofo in adjudication and lineage authority has been affected by colonial and post-colonial state systems. One commentary states that in some parts of Igboland, the ofo institution is no longer regarded as the great adjudicator it once was.

The consumption of nzu as edible chalk faces serious health critiques. Medical sources report that lead in calabash chalk can cause anaemia, nerve damage and other health problems. These concerns are pushing some communities to restrict or modify certain uses of nzu.

The symbolic language of nzu and ofo may not be fully understood by younger generations. One study on colour symbology in Igboland found that many respondents reported less use of traditional chalk (nzu) for symbolic communication than previous generations.

The adaptation of nzu and ofo rituals also points to new paths:

- Cultural education: The heritage value of nzu and ofo is becoming part of cultural revival and teaching programmes. This helps younger Igbo people connect with tradition in a modern context.

- Hybrid ritual practices: In some families and communities, traditional items like nzu and ofo are still used alongside Christian or modern religious practices. For example, devotional acts may include nzu in naming ceremonies, house blessings or ancestral remembrance, even in Christian homes.

- Ethical leadership: The symbolic power of ofo is being used to reinforce contemporary leadership ethics. One article notes that the ofo staff reminds leaders that true authority is not about power or dominance but about service, justice, and welfare of the people.

Fundamentally, the nzu and ofo rituals have not simply been frozen in time. They continue to matter in modern Igbo life, though their forms, contexts and interpretations are changing. The challenge and opportunity lie in preserving their core values of purity, truth, justice and ancestral connection while adapting them for health awareness, modern leadership ethics and cultural education.

In Conclusion …

Nzu and Ofo rituals remain among the most enduring pillars of Igbo spirituality and cultural identity. Even in today’s rapidly changing society, they continue to represent the heart of truth, purity, peace, and ancestral connection within the Igbo worldview. While modernization and religious transformation have altered how these traditions are practiced, their essence endures in both symbolic and practical forms.

Across Igboland, Nzu ritual still marks moments of blessing, welcome, and spiritual cleansing, while the Ofo continues to embody justice, legitimacy, and ancestral authority. Together, Nzu and Ofo rituals remind Igbo people that moral conduct, honesty, and communal harmony are sacred responsibilities tied not only to the living but also to the unseen forces that guide life.

In contemporary times, these rituals have found new expression through cultural education, art, and community heritage preservation. As younger generations seek to reconnect with their roots, Nzu and Ofo rituals serve as a profound reminder of who the Igbo people are, where they come from, and the timeless values that continue to hold their communities together.

Ultimately, preserving the knowledge and meaning of Nzu and Ofo rituals is not just about keeping tradition alive, it is about safeguarding a living philosophy that celebrates truth, purity and the unbroken link between humanity and the divine.

References

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269277866_Ofo_as_a_Global_Cultural_Resource_and_Its_Significance_in_Igbo_Culture_Area

- https://ichekejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/25.-Oath-Taking-and-Covenant-Making-Diplomatic-Methods-for-Conflict-Reconciliation.pdf

- https://www.idosr.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/IDOSR-JCISS-21-68-77-2016.-UME.pdf

- https://twocents.space/insight/the-significance-of-nzu-white-chalk-in-igbo-culture-496/

- https://gjrpublication.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/GJRHCS52122.pdf

- Kanu, I. A. “The Ofo In Igbo: Arts, Crafts and Symbols.” (2020).

- “ỌFỌ: The Emblem of Justice” — Nigerian Journals Online (article on ofo as symbol).

You might want to check this out …